History in Black Light

September 13, 1995

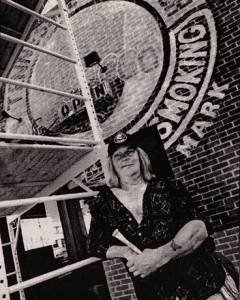

Mark Arminski and The Return of the Rock Posters

Mark Arminski and The Return of the Rock Posters

“I’m still doing it for the hell of it,” says Detroit artist Mark Arminski of the luminous rock concert posters that have made him one of the nation’s best-known poster artists. But with an invitation to participate in a historical retrospective of the rock concert poster at the opening of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, it’s clear that ‘for the hell of it’ is beginning to pay off. Five years ago, Arminski began designing flyers for friend’s gigs, like the late MC5 frontman Rob Tyner and the proto-all-girl band Vertical Pillows. Even now, with a collection of his work at Wyandotte’s Java Joe’s the RRHOF opening showing, he tempers his growing success with humility. “I don’t have to do this for a living,” he says. Which is true, since he is already an accomplished muralist, painting restaurant interiors for Monterrey Cantina, Mr. B’s and others. But if not for living, he clearly wants to pursue poster art to, as he puts it, “get my name out there.”

It already is. Last spring, he was highly visible in ‘Juxtapoz’ magazine’s “The History of Rock Art Posters.” There Arminski, together with Texas’ Frank Kozik, Cleveland’s Derek Hess and California’s Emek and Coop, were anthologized as poster art’s next generation. Arminski’s name is known to both collectors nationwide and to local hipsters who can find his new work up at local record stores.

And now, at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, his posters hand alongside those of former Detroiter Gary Grimshaw, whose concert posters for the Grande Ballroom defined an era of psychedelic music and culture. It’s a fitting parallel, as the two artists have served as visual historians for their respective eras. Grimshaw’s bulbous, bold hand-lettering, and his Daliesque style captured the exaggerated culture of such post-blues acts as Cream and the MC5.

Likewise, Arminski’s trademark experimental colors, exact imagery and wry wit captures ’90s rock in all its irony. Born in 1950, Arminski traces his roots directly back to poster-dom’s first generation. As a teenager, he collected the work of Detroit’s Grimshaw and Stanley Mouse and San Francisco’s “Family Dog” posters by legendary Grateful Dead artist Rick Griffin. Pulling out a vintage Griffin, he cites the organic quality of the type, the ‘little flaws’ ha says have the work of the ’60s its vitality. “It’s just amazing,” he says. “Their sense of line, how they did all their lettering by hand. You just can’t get that with a computer.” Cranking out his silkscreened, full-color works at the rate of one a week, Arminski has been making posters for virtually every major rock concert and favorite local band in southeastern Michigan (and Ohio) for over a year now, from national heroes like Eric Clapton to local acts like Sponge (one of his earliest clients) and Spank.

He spends most of his week in his studio, headquartered at Madison Heights’ SF&A, Inc., his printer for the last year. There, samples of his posters hand indiscriminately around the airy postindustrial building, along with those of Cleveland’s Derrick Hess, whose work SF&A also prints. Arminski prints his posters in limited editions of 500, which are divided up between the bands and promoters. His publisher, Rick Manore, also gets his share for future licensing to dealers like San Fran-via-Ann Arbor’s Artrock, where Arminski’s Nine Inch Nails poster for last fall’s Pine Knob show is still a top seller. Art rock posters are one of the last great grass-roots art forms: a kind of ornery conjunction of graffiti tagging, rock culture and word of mouth advertising. The poster has risen in popularity and visibility in direct proportion to rock’s ever-expanding horizons.

It’s no surprise that Detroit, as one of the country’s most visible markets for new rock, should also produce some of poster art’s finest names. Detroit artists include Arminski, as well as kitsch caricaturist Glenn Barr and the more cerebral Mark Dancey, of ‘Motorbooty’ fame. But Arminski, now 45, is less angsty than his contemporaries, who sometimes chock their work with their own fine art caricatures and other heavy-handed imagery. “I guess I used to do things for shock value,” he explains. “Like back during the whole Jesse Helms/NEA cutting thing, when I did a show of explicit stuff with Keith from Noir Leather as a protest. I’ve been grant-funded before and I know how important that is.” (Arminski turned down a H.O.R.D.E. poster offer this year: “Too many restrictions, all that control shit,” he says flatly.) “But with the posters, they’re there to serve a purpose. I mean, some of these guys, you can’t tell what band the poster’s for because all you can see is their artwork.”

As such, Arminski works more from the public domain than his more iconoclastic, post-punk brethren. Almost utilitarian, his posters are often built around an image of the band itself, tweaked with a subtle sense of humor. For the Beastie Boys show at Cobo, last spring, Arminski turned to the ’70s TV shows mined by the rap trio’s ‘Sabotage’ video. A lollipopping Kojak and his “Who Loves Ya Baby?” became the poster’s central image. Often, it’s the artists themselves who are most wowed. Frequently, they call asking for extra copies for themselves and their cohorts. For a recent Primus poster, Arminski drew a fish image inspired by the band’s CD jacket, which for him, constantly on production deadline, was a real time commitment. Head Primus Les Claypool was floored, likewise requesting extra prints. “He couldn’t believe I would put this kind of time and energy into a poster for them.” But no matter how many rock eccentrics praise his time and effort, Arminski’s got a serene perspective on his role in rock merchandising. “I know people are buying it for the band name,” he says, and goes, as always, back to work.